How Little Training Can You Get Away With?

Chris Carmichael, Founder and Head Coach of CTS discusses times when life gets in the way and other priorities eliminate or dramatically reduce available training time

Although I spend most of my time trying to help athletes fit more training into their busy lifestyles, there are times when life gets in the way and other priorities eliminate or dramatically reduce available training time. There are also times, particularly at the end of a long season full of events and competitions, when athletes need a break. These scenarios beg the questions: how little training can you get away with and preserve endurance performance, and for how long?

As an athlete, it’s safe to say your goal and desire is to train more than the bare minimum required to preserve performance, but investigating the minimum amount of exercise required to elicit a training response helps us to understand the dose-response relationship as athletes add more training volume, frequency, and intensity. It is also important because studies have shown that minimizing the decline in performance between seasons is associated with greater performance improvements during the next season (Mujika 1995, and Rønnestad 2014). As I’ve told athletes for many years, it is very difficult to make year-over-year improvements when you must spend four to six months just losing and regaining fitness.

A May 2021 review in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research by Speiring et al took a fresh look at the minimum effective dose of exercise. As we head into winter and the impending Holiday Season that now seems to stretch from October to January, it may be comforting to know that – if you must – you can get away with significantly reduced training without losing much of your hard-earned fitness.

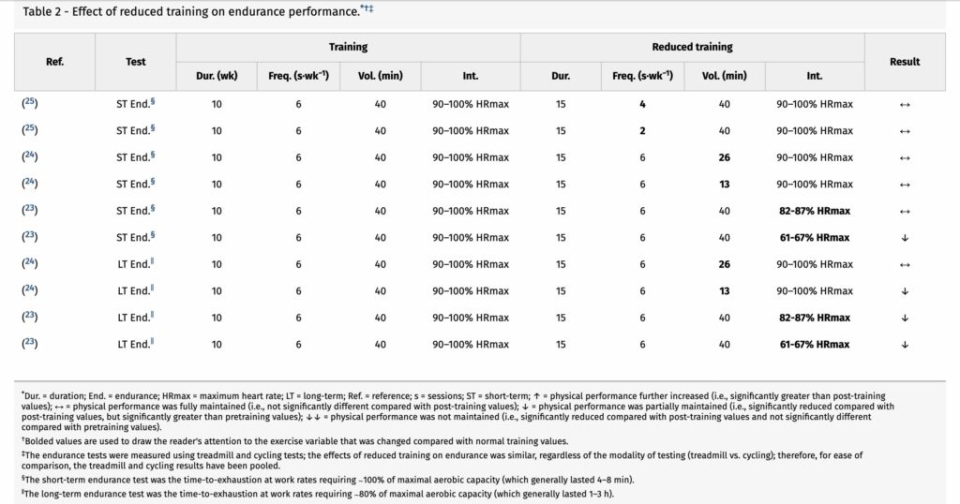

It all depends on how you reduce your training, what components of exercise you keep doing, and what aspects of endurance performance you’re trying to preserve. The review specifically defined short-term endurance as “time to exhaustion at workloads equal to ~100% of VO2 max, which generally lasted 4-8 minutes” and long-term endurance as “time to exhaustion at workloads equal to ~80% of VO2 max, which generally lasted 1-3 hours”.

Reducing Frequency

As with a lot of sports science research, it is important to consider the fitness level and training experience of the subjects. More studies are conducted with untrained or moderately fit subjects than with trained athletes. For generally active people, reducing training frequency from 6 sessions per week to as few as two sessions per week (keeping session duration constant at 40 minutes/workout and intensity constant) for five weeks didn’t significantly reduce VO2 max (Hickson and Rosenkoetter 1981). However, newer studies (90’s and 2000s) with trained subjects–more relevant to the audience of this blog–indicate that reductions in training frequency should be kept to 20%-50% which is basically reducing frequency by one day per week (5 days to 3 or 4, for instance).

Reducing Volume

What about shorter rides? As a matter of practicality, I am always leery of removing training sessions from an athlete’s weekly schedule. Once that time is open to be allocated to something else, it can be hard to get it back. So, even though you can reduce frequency and maintain performance, I’d rather keep the number of training days constant and change what you’re doing within those sessions.

If you’re riding six days a week (I’m using that example because it’s what the main studies referenced in Spiering’s used), what happens when you cut the duration of those sessions by 33% of 66%? In another experiment by Hickson, when intensity and frequency were constant for a 15-week period, short-term endurance (4- to8-minute efforts) was largely unaffected by either a 66% or 33% drop in per-session training duration. Long-term endurance (80% of vo2 max for 1-3 hours) was retained with the 33% reduction but not with the 66% reduction in per-session volume.

It should be noted that the initial workout durations in Hickson’s studies were only 40 minutes, and the reduced-volume sessions were 26 and 13 minutes, respectively. The intensities were high (90-100% of maximum heart rate), too. As a result, the workout parameters aren’t a perfect match for workouts that are typical for endurance cyclists (which are longer at lower intensities). However, the Spiering review points out that research on tapering – which is similar but not the same as reduced training – indicates that training volume can be significantly reduced (60-90% over 4 weeks in the case of tapering) and preserve or even improve performance.

Reducing Intensity

Here’s where things get interesting. Reducing frequency and/or volume didn’t have much of a detrimental effect on endurance performance, but backing off on the intensity did. In a third Hickson study, when frequency was held at 6 workouts per week and volume was held constant at 40 minutes per session, but intensity was reduced to either 82-87% of max heart rate or 61-67% of max heart rate, long-term endurance (1-3 hours) performance dropped in both groups, and short-term endurance (4-8 minutes) was only retained in the 82-87% group. This too, bears some similarity to tapering research, where the successful formula for preserving or improving performance is to reduce volume and training frequency but retain intensity. The difference here is that tapering is typically a 4-week period and the reduced training studies lasted 15 weeks.

The table below illustrates the various combinations mentioned above:

Final Answer?

This is sports science, so you know there’s no final answer. Each new study or review adds context and new information, but the Spiering review reinforces the idea that exercise intensity is the key variable for maintaining endurance performance during a period of reduced training. It also seems clear that maintaining performance is easier than building fitness and improving performance. It doesn’t take that much – two or three workouts, about 60 minutes each, that include some hard intervals – to retain the vast majority of the adaptations you’ve already earned.

So, when the weather turns cold and cruddy, end-of-the-year reports and projects keep you at work late, and family trips to your long-lost uncle’s house steal away precious training time, don’t fret. Do what you can, as frequently as you can, and just make sure to include some intensity. You might be treading water, so to speak, instead of making forward progress, but you’ll still be setting yourself up with a chance to exceed your 2021 performance level in 2022.

To find out more, please visit: https://trainright.com/how-little-training-can-athletes-get-away-with/

FREE 14 DAY MEMBERSHIP TRIAL

Gran Fondo Guide fans, click on the image above and get TrainRight Membership for a 14 day no obligation trial. TrainRight Membership comes with a 30-day money-back guarantee!

About CTS

As it has since 2000, Carmichael Training Systems leads the endurance coaching industry with proven and innovative products, services, and content. And the results speak for themselves; no other coaching company produces more champions, in such a wide variety of sports and age groups, than CTS.

For more information, please visit: https://trainright.com